The Jewish Week is expanding their roster of rabbinic commentators and Reb Blog got called up to the plate this week. (thanks Jonathan)

Here's my drash on this week's Torah portion:

| Shabbat Shemot |

| Revolution By The Nile: Defiance In The Global ‘Egypt’ |

Fifteen years ago, I was a passenger on a rusty bus headed out of Egypt. Like many of the young Jewish college kids who had found their way to Cairo on a tourist visa, my weeks in Egypt were a revelation to me. I saw thousands of families living in aluminum shacks in an old graveyard. I saw throngs of children impacted by water-borne diseases begging in the streets. I heard screams in the night during a power outage. That was all behind me as the bus winded its way through the Sinai and up ahead I could see blue and white flags waving in the mid-day desert sky. I was headed back home, back to the comfort of my friend’s apartment in Jerusalem, the café on the corner, the cozy chair on the terrace.

The rise from poverty to wealth is one way we continue to view this week’s parsha. We read: “And they cried out to God because of the hard work” [Ex. 3:23], and we are thankful for the outstretched arm of the Holy One that allowed us to elevate our economic status from bottom rung worker to land of milk and honey homeowner. We lean on pillows and sip wine. But sitting on that porch chair, I couldn’t help but flashback to the thousands of poor Egyptians I saw, and wonder: When will they have an “Exodus” of their own?

This concern was at the heart of “liberation theology,” the title given to the South American Christian movement of the 1970s that had its roots in Marxism and used Exodus as a springboard for revolution. Exodus, for Peruvian priests like Gustav Gutierrez, was not about leaving for a promised land, but about transforming nations that had become “Egypt,” into something more than slave camps. Bob Marley sang in 1973: “Today they say that we are free, only to be chained in poverty. Good God, I think it’s illiteracy. It’s only a machine that makes money. Slave driver: the tables are turning!”

To say that Marxist revolutions have not produced such great results would be an understatement. But still, I read this week’s parsha and ask myself: Is there something written in our Torah that is not about leaving Egypt, but about transforming it?

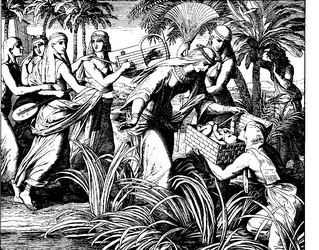

I needed the 1,800-year-old comments of Rabbi Shimon Bar-Yochai to realize that it is all there in Chapter Two. Chapter Two recalls how Yocheved, Moses’ mother, hides her child and then asks her daughter Miriam to place the boy in a basket on the river Nile. Then the text goes into crisp detail about Pharaoh’s daughter’s discovery of the child. And this is where Rabbi Shimon Bar-Yochai’s teachings come into play.

In the Babylonian Talmud, in Sotah 12b, Bar-Yochai asks: Why is Pharaoh’s daughter going down to the Nile? He states that she is going down to the Nile to both metaphorically and literally “cleanse herself of her father’s idolatry.” When she asks her servant to fetch the baby, her servants “warn her that she is violating her father’s decree.” And how does she respond? She miraculously “stretches out her own hand.”

I like to read this together with Ibn Ezra’s 12th century commentary on the verse “And she called his name Moshe, and she said: Because I pulled him out of the water” [Ex. 2:10]. First Ibn Ezra notes that the daughter of Pharaoh gives this adopted baby a Hebrew name, and clarifies that the name she chooses, Moshe, actually means “He who pulls.” Then Ibn Ezra suggests that either she “learned Hebrew or she asked a Hebrew about the name.” So, in other words, not only does she seek to cleanse her father’s idolatry and violate his decrees, but to name his grandson with the provocative Hebrew name “He who pulls.”

The 13th century French scholar Hizkiya Hizkuni understood this to be a bit of prophecy — she thinks that Moses will “pull” the Jewish people out of Egypt. But we might take his idea even further: Moses will also pull apart the system of oppression that suffocates Pharaoh’s daughter and the Egyptian people. Like the German Christian martyr Sophie Scholl who opposed the Nazi regime, Pharaoh’s daughter engages in a defiant act that both reaches out with compassion to the oppressed and aims to save the soul of her nation. In the end, her act destroys not only her violent father and his entire army, but the system that made Egyptians into snitches, prison guards, and taskmasters.

So what do we learn from this week’s parsha? And how does it relate to the continued presence of “Egypt” — slavery, poverty, and hard labor - of our day? Are we truly free when four million people (most of them women) are being trafficked between borders? I sense that the Torah includes Pharaoh’s daughter’s story to teach us that it is not only the Jewish people who suffer under the “Egypts” of the world and must boldly defy the Pharaohs, but all those who are forced into submission or silence. Even those in the royal courts. The Torah reminds those of us in cozy chairs that we all must go down to the Nile, cleanse ourselves of the desire for God-like power, and take the abandoned poor into our arms.